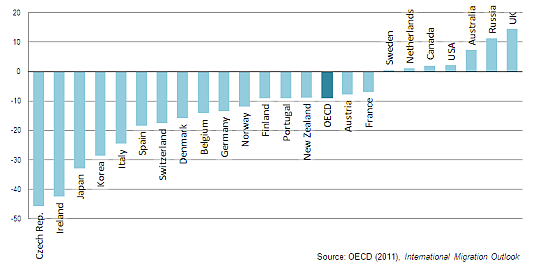

The decline is particularly marked in Asian OECD countries and in most of Europe, notably the Czech Republic, Ireland, Italy, Spain and Switzerland. In Europe, movement between EU member states fell by 22% in 2009. In contrast, permanent migration to Australia, Canada and the United States increased slightly in 2009. Temporary labour migration is especially susceptible to shifting demand and declined by 17% in 2009.

Declines in permanent migration

% Change in inflows of permanent immigrants, 2008-2009

Given the severity of the crisis, migration has fallen less than might have been expected, says the OECD. This may reflect the impact of demographic trends, notably in Europe, where ageing populations and falling fertility rates will mean a continuing demand for skilled and unskilled workers. Family and humanitarian migration are less affected by economic downturns.

“Demand for labour migration will pick up again,” said OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría, presenting the report in Brussels, together with EU Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion László Andor and EU Commissioner for Home Affairs Cecilia Malmström. “Globalisation and ageing populations make that a certainty. Governments must do more to develop legal labour migration channels and foster better use of immigrants’ skills.”

The drop in migration coincided with declining job opportunities. Young immigrants have been especially hard hit by job losses, as have workers in construction, finance and retail. Immigrant employment has risen on the other hand in education, health, long-term care for people and domestic services. More migrant women have also joined the labour force to compensate for job losses among male migrants, according to the report.

Migrants are also slightly more likely than native-born persons to start a new business in most OECD countries, says the report. Businesses started by immigrants create significant numbers of jobs. Thus, governments need to eliminate specific obstacles to enterprise creation and growth by immigrants in order to help spur job creation.

The number of students coming to study in OECD countries from abroad continues to rise, reaching 2.3 million in 2008, the most recent year for which figures are available, an annual increase of 5%. Nearly one in five came from China, totalling 410,000. On average across the OECD, about one in four will stay, providing an increasingly important source of skilled workers.

Migration from China also accounts for about 9% of all inflows, followed by Romania (5%), India (4.5%) and Poland (4%).

The report makes four key recommendations to help governments improve management of migration flows:

- Get the facts into the public domain. Most migrants are well integrated in economies and societies. Asserting otherwise undermines equal opportunities for migrants and their children.

- Broaden co-operation between OECD and origin countries, as well as between governments and employers. This will help improve recruitment of legal migrants, reduce flows of illegal migrants and boost economic opportunities in developing countries.

- Strengthen integration efforts. Integration should be seen as a long-term investment, not a short-term cost. Too often, excessive geographical concentrations of disadvantaged and low-educated immigrants have been allowed to build up, with devastating effects on school environments and results.

- Give everybody a fair chance to succeed. Naturalisation should be facilitated and encouraged to guarantee equal rights for all.